There’s a popular worship song that I always hope doesn’t get sung before I speak in churches and at conferences, since the lyrics stand in sharp contrast to my message. The chorus goes like this:

This is amazing grace

This is unfailing love

That You would take my place

That You would bear my cross

You lay down Your life

That I would be set free

Oh, Jesus, I sing for

All that You’ve done for me

The discordance comes from the song’s idea of a Jesus who suffers so that we will not have to–a Jesus who, in other words, came so that we could be set free to live lives unlike his. The song celebrates the idea that Jesus bore our crosses–an idea that is very different than Jesus’ own statement in Matthew 16:24,

Whoever wants to be my disciple must deny themselves and take up their cross and follow me.

Lest the meaning be unclear to us (or uncomfortably clear, as is more often the case), Peter restates it in 1 Peter 2:21,

For you have been called for this purpose, since Christ also suffered for you, leaving you an example for you to follow in His steps.

According to Peter, Jesus did not take up his cross so that we would not have to. He took up his cross so that we would choose to do so also.

Our cross-carrying doesn’t save anyone, unlike Jesus’. But our cross-carrying echoes his, points to it, re-presents it, makes it more than a platitude when we say to our enemies, “Christ died for your sins.” Because when the words are accompanied by our cross-carrying actions, we are really saying, “Believe me when I tell–and show–you that Christ died for your sins, for there is no other explanation for my actions toward you who are persecuting me.”

This hardly leaves the rest of the world “free” and us Christians burdened. Christ’s death on the cross shows us that our definitions of “life, and life abudantly” have been warped by sin. That’s why in Matthew 16:25, the verse directly after Jesus summons us to carry our crosses, he says,

For whoever wants to save their life will lose it, but whoever loses their life for me will find it.

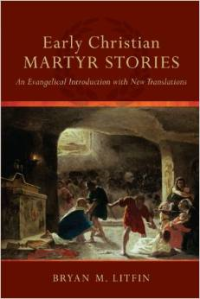

This is Part II of our series, God of the Persecuted: What The Lives Of Persecuted Believers Teach Us About The Nature Of God. (Click here to see Part I.) In Part II, what we’ve learned is that the existence of two millennia of martyrs shows that the cross is intended as a pattern for normal Christian living, not a punctiliar event that exempts us from the pattern. The cross sets us free not from carrying it but from a cross-less life, which, as Jesus says, is–no matter how it may appear–the essence of burden, the definition of lostness.

To turn the language of the worship song upside down, Jesus did not come to carry our cross or to set us free from laying down our lives. He came to show us that carrying our cross and laying down our lives are not only the appropriate response to but also the means of grace by which we come to experience God’s amazing grace in deeper and more amazing ways.

The writer of Hebrews phrases it like this, in Hebrews 11:32-40:

32 And what more shall I say? I do not have time to tell about Gideon, Barak,Samson and Jephthah, about David and Samuel and the prophets, 33 who through faith conquered kingdoms, administered justice, and gained what was promised; who shut the mouths of lions, 34 quenched the fury of the flames,and escaped the edge of the sword; whose weakness was turned to strength;and who became powerful in battle and routed foreign armies. 35 Women received back their dead, raised to life again. There were others who were tortured, refusing to be released so that they might gain an even better resurrection. 36 Some faced jeers and flogging, and even chains and imprisonment. 37 They were put to death by stoning;[e] they were sawed in two; they were killed by the sword. They went about in sheepskins and goatskins,destitute, persecuted and mistreated— 38 the world was not worthy of them. They wandered in deserts and mountains, living in caves and in holes in the ground.

39 These were all commended for their faith, yet none of them received what had been promised, 40 since God had planned something better for us so that only together with us would they be made perfect.

And then in Hebrews 12 he exhorts us to emulate them.