As a “non-state actor” (more on this term in a moment) who faced criminal charges during the Moon administration for my North Korea-related work, I was asked shortly after the May 10 election of Yoon Suk Yeol whether I was now expecting better days.

Another NK-related group had given their emphatic affirmative answer at that time, launching 1 million leaflets to North Korea bearing president-elect Yoon’s face.

But as the CEO of an NGO whose offices were blockaded by police under a prior conservative administration, I remain skeptical. After two decades as a North Korea-related non-state actor based in South Korea, it has been my experience that a change in administration may change which non-state actors are favored, but it has not yet resulted in greater tolerance of North Korea-related non-state action overall.

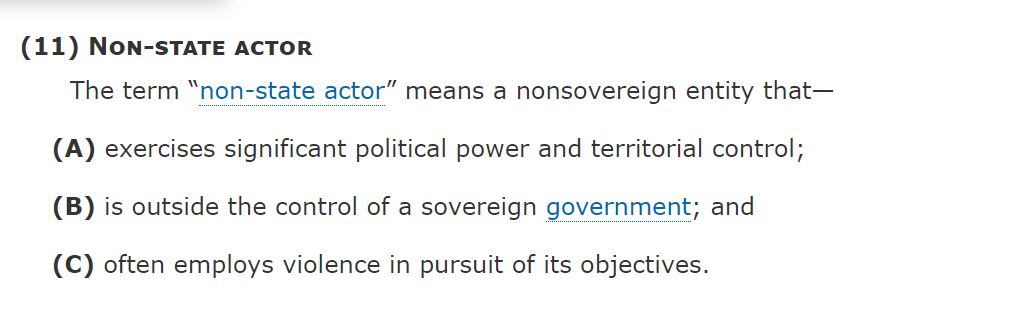

The problem is not uniquely Korean. Section 6402 of the US Code on Foreign Relations and Intercourse defines a non-state actor as “a nonsovereign entity that— (A) exercises significant political power and territorial control; (B) is outside the control of a sovereign government; and (C) often employs violence in pursuit of its objectives.” Even the Oxford Dictionary raises states’ eyebrows, defining a non-state actor as “an individual or organization that has significant political influence but is not allied to any particular country or state.” Geun Lee and Kadir Ayhan (the latter an appointee to President Yoon’s National Unity Committee) aim for a more neutral characterization of non-state actors as individuals and informal and formal entities who are “relevant to international relations and operate at the international level (including transnational)” but who are “not representatives of states” (p. 58).

Defining non-state actors in relation to states works when the definition of “state” is itself stable. But as the Hague Center for Strategic Studies notes, “The nature and extent of state authority and the ways in which a state exerts its authority have dramatically changed. While the state’s core task used to be to ensure security and protection for its citizens, nowadays the state provides social security, healthcare, transportation, education, and many more services well beyond enforcement of the law.” (p. 142)

In South Korea, the state’s “core task” related to North Korea is reshaped by each incoming administration. If North Korea is the state’s “main enemy”, protection against the perceived North Korea threat becomes a core task. If the state envisions “a permanent and peaceful Korean peninsula peace regime”, as in the Panmunjom Declaration, then protection against perceived threats to that peace regime becomes paramount.

However the core task is construed, South Korean administrations have been ironclad in their agreement that no North Korea-related actors may operate outside of state purview. The logic is: If anything moves from South to North, the North treats it as a direct action of the South Korean state. All activity by North Korea-related non-state actors is considered provisional and may be curtailed by the state at any time, as according to national security concerns, or policy concerns portrayed as national security concerns. The idea of a North Korea-related non-state actor is thus rendered dangerous or meaningless.

North Korea-related non-state actors based in South Korea have had four options in response. First, breathe a sigh of relief when an administration is elected which regards the non-state actor’s work as compatible with the administration’s policy. Second, when it’s not, lay low and hope for better days. Third, seek the patronage of partners (e.g., other states, funding sources, media) strong enough to at least give the new administration pause about curtailing the work. Fourth, lawyer up. Most North Korea-related non-state actors move pragmatically between all four with relatively little friction.

What I hope for from the incoming administration is more than the predictable reshuffling of the non-state actor deck. I hope instead for a new hands-off attitude toward the deck overall.

It is not a small hope. What I am seeking is the recognition by the South Korean government of a category of North Korea-related non-state action which it recognizes is outside of its purview to regulate or restrict. I am not seeking the creation of a special license or exception for which qualified NGOs may apply. I am seeking the government’s recognition of something which belongs to all of us by right.

That final phrase sounds like a rhetorical flourish, but it is in fact a precise term with solid international provenance. Human rights advocate Andrew Clapham recounts how someone once responded to the request for a definition of the term “non-state actor” by saying that it meant simply “all of us”.

“All of us” proves to be a superior definition to the others mentioned so far because it stays the same regardless of how states (re)configure themselves or their policy and security agendas. Article 1 of United Nations General Assembly Resolution 53/144, Declaration on the Right and Responsibility of Individuals, Groups and Organs of Society to Promote and Protect Universally Recognized Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms, adopted Mar 8, 1999, says, “Everyone”—that is, all of us—”has the right, individually and in association with others, to promote and to strive for the protection and realization of human rights and fundamental freedoms at the national and international levels.”

That last phrase is important. I am entitled to engage in North Korea-related non-state work in South Korea not only on the basis of my own human rights, but also on the basis of my striving for the protection and realization of the human rights of North Koreans. “All of us”, in other words, have the right and responsibility to realize the human rights of North Korean people and to act in accordance with those rights, whether such actions are in accord with a given administration’s policies or not. It is not our status as South Korean citizens or NGOs in good standing which gives us this right, but rather our inalienable status as non-state actors, which is to say, as human beings acting individually and in association with others, as according to the UN Declaration.

Likewise, North Koreans, as human beings acting individually and not as an extension of the North Korean government, possess an inalienable right to connect with “all of us” as we jointly realize our human rights. Article 5 of the Declaration says, “For the purpose of promoting and protecting human rights and fundamental freedoms, everyone has the right, individually and in association with others, at the national and international levels: (a) To meet or assemble peacefully; (b) To form, join and participate in non-governmental organizations, associations or groups; (c) To communicate with non-governmental or intergovernmental organizations.”

Although the UN human rights document corpus recognizes that states are primarily responsible for ensuring the enjoyment of human rights, it nowhere accords them the role of defining, interpreting, granting, or regulating them. To the contrary, it is these very things that the documents demand that states refrain from doing. States may engage in negotiations with other states in ways that may (and inevitably will) impact human rights. But they may not restrict or restrain the exercise of the human rights of their citizens or the citizens of other states in the process of achieving their policy designs. One can’t, for example, foster a “peace regime” by suspending for even a single citizen, even temporarily, rights recognized as inalienable.

Note that more is asserted by the UN Human Rights agreements than that governments make provision for sanctions exemptions for humanitarian aid. Human rights define the “floor” of interaction between “all of us” humans with which states may not tamper. That means when I talk to a North Korean person, the burden of proof is not on me to establish that that contact is not an act of espionage. The burden of proof is on the state to establish that it is.

My comments here are admittedly and intentionally restricted to a very specific type of activity. They do not cover, e.g., NGOs seeking to undertake vaccination projects with the NK government, nor educators seeking to contract with the NK government in order to teach there, because states do not possess human rights. Engaging with, by, or through states is by definition a means to an end, entailing questions beyond the direct and immediate human rights guarantees which accrue to us inalienably as individuals in association with other individuals, nationally and internationally. Thus, my comments here cover only non-state actors from South Korea interacting directly with non-state actors in North Korea in the mutual enjoyment of our human rights. These are rights that are not granted by states and thus may not be curtailed by them absent the state’s proof that something specifically compromising state security is afoot. That standard of proof, according to the UN Human Rights document corpus, is real and not a matter of generalities, suspicions, or accusations.

One could ask, “Yes, but does such a narrowly delimited right amount to much? Is there not more to be gained through state actors acting in policy alignment with suitable NGOs dutifully in tow?” The most important response is: It doesn’t matter. The enjoyment of human rights is not the means to any end. It is simply the predicate of our humanity.

On the other hand, imagine if a change in presidential administration left untouched the human interactions between NKs and SKs as they realize their inalienable human rights, even if only for “all of us” in South Korea. If the South Korean government refused to interfere with humans acting outside of state strictures north and south in the enjoyment of their universal rights, even if only by phone, Internet, or, yes, even balloon, would the impact on North-South relations be insignificant?